Arbitral Award, Supreme Court Sustain China’s Historic Rights

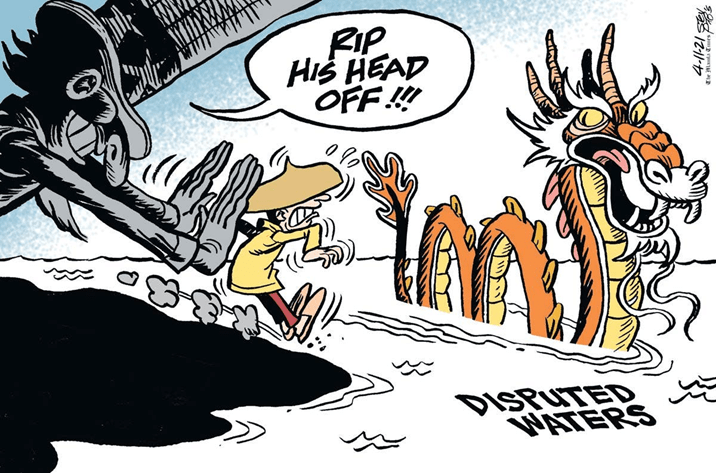

Part One of Two: Poking the Bear or Chasing the Dragon?

Returning from a trip from Germany and Czechoslovakia, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., said the Philippines was not “poking the bear” or acting at the behest of the United States in countering the growing threat from China’s sweeping claims in the South China Sea.

Besides giving us a hint on who could be writing his speeches, this drew my curiosity because of the seeming incongruence of his use of the American idiom in reference to China.

The Cantabrigian meaning of the idiom is “to intentionally make or try to make someone angry or offended, especially someone more powerful than you”. The literal meaning is underscored by a compelling historical short story, published in the Chicago Eagle Newspaper on April 8, 1893.

Wiktionary points, however, to its connotation that means “to anger or threaten Russia and start a war with Russia.”

China is more appropriately referred to as the dragon. But a ghostwriter’s careless shift of a pen could have been more pejorative to the president.

The idiom “chasing the dragon” is of Cantonese origin from Hong Kong, but is more prominently known as “foily” in Australian English. It refers to inhaling the vapor of a powdered psychoactive drug off a heated sheet of aluminum foil.

A broader use of the term “chasing the dragon” means the elusive pursuit of a high equal to the user’s first in the use of a drug, which after acclimation is no longer achievable. In this manner, the idiom can refer to any recreational drug administered by any means.

The implication would have been derogatory to Marcos Jr who is rumored to do cocaine.

But before his detractors could float their malicious minds, the president quickly took a step back and announced he would not allow the use of military bases in the country for offensives against China, noting the Philippines has “no interest” in attacking China or any country.

The unfortunate idiom “poking the bear” was obviously provoked by an expose that appeared in the Manila Times that as of April 2023, China presented 11 concept papers, “but these were met with inaction by the Marcos administration.”

Expose’

The whistleblower said the Chinese government tried to formally discuss the details of the paper by sending its Vice Foreign Minister Sun Wedong in May 2023. The proposals were also raised as recent as two months ago in the 8th Bilateral Consultation Mechanism (BCM) on the South China Sea in Shanghai on January 17, 2024.

“We expected the Philippines to agree to discuss the initiatives and go into details, but until now, after waiting for almost a year, we have not received any response or feedback,” the Chinese official said.

As expected, the response of the Department of Foreign Affairs was neither here nor there, sounding lame. While denying that in no way did it ignore the Chinese proposals, it claimed, “Upon receipt of the Chinese proposals, the Philippine Government had immediately undertaken serious study and consideration of all of them.”

Resorting to the usual legalese, the DFA said it had lengthy and in-depth consultations with various government agencies and held several rounds of discussions but found that some of the proposals if pushed would equate to violating the Philippine Constitution.

The Chinese diplomat who spoke on condition of anonymity, however, said that some of the proposals were submitted upon the request of the Philippine side, so how could they be unconstitutional?

DFA sidestepped saying “While a few proposals were deemed somewhat workable, many of the remaining Chinese proposals were determined, after careful study, scrutiny and deliberation within the Philippine Government, to be contrary to our national interests.”

The December 2023 update of Pulse-Asia’s “most urgent national concerns” point to the South China Sea issue, specifically “protecting Philippine territory against foreigners”, at a nominal 6% when compared to many economic issues, top of which was at 72%.

Handbrakes engaged

DFA also alluded to a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” where “China insisted on actions that would be deemed as acquiescence or recognition of China’s control and administration over the Ayungin Shoal as China’s territory.”

“As Ayungin Shoal is a part of the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines, the proposal of China could not be considered by the Philippines without violating the Philippine constitution or international law,” the DFA added.

But that is distortion because the Arbitral award itself has ruled out EEZ application at Ayungin as it considered the area as “quintessentially militarized” in its Paragraph 1162.

Throughout the DFA official lines, the pattern is that it buried the Chinese proposals considering that not one of the proposals was ventilated before the general public. The absence of transparency created the pervading perception that the Philippine government is under duress from a third party.

I heard a simile likening Philippine-China relationship to a car where a passenger has applied the handbrake since February 2023 when four additional sites were added to the American EDCA bases.

The Philippines had long promoted the cliche that Chinese actions are in violation of international law, but all its assertions lead to a single ruling of the 2016 Arbitral ruling that China’s nine-dash line (now ten-dash line) has no legal basis.

With this, the entire Philippine position stands. Sadly, without it, the entire Philippine position collapses.

It was necessary for the American and British lawyers of the Philippines in the arbitration to demolish by lawfare China’s sovereignty in the South China Sea. The strategy was to plant even just a single paragraph which can be used by “rules-based” propaganda clouding 1201 other paragraphs in the same Arbitral ruling of 479 pages.

Asymmetry

China’s claim is on the level of sovereignty over territorial sea, while that of the Philippines’ is on sovereign rights over exclusive economic zone. This presents an asymmetry that is in favor of China because sovereign rights cannot overlap sovereignty, exclusive economic zones cannot protrude territorial seas of another state.

The Philippine assumption is that Paragraph 278 nullifies China’s sovereignty claim, in effect removing the asymmetry between the two claims. I consider this, however, as a fragile single foundation of entire architecture of the assumed legitimacy of the Philippine claims in the South China Seas.

Let us render a linguistic analysis of Paragraph 278 which states, “…the maritime areas of the South China Sea encompassed by the relevant part of the ‘nine-dash line’ are contrary to the Convention and without lawful effect to the extent that they exceed the geographic and substantive limits of China’s maritime entitlements under the Convention.” (Italics, mine)

What it is actually saying is that if you want to legitimize the nine-dash line, you will have to look elsewhere because UNCLOS cannot do that.

I find it therefore dumb for our government agencies especially the coast guard, national defense, foreign affairs and the presidency accusing China of “violating international law” without specifying what it violated and how.

Often these pea-brains are just swashbuckling Paragraph 278 of the Arbitral ruling based on UNCLOS which is only a single treaty that is obviously not the entirety of international law. According to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, there are over 250,000 international treaties that aim to foster global cooperation.

Rebuttal

But China’s rebuttal is substantial and reduces Marcos Jr’s statement into an obnoxious canard. There is no need for any country in the world to recognize the nine-or-ten-dash line because China’s sovereignty claims are not based on that map, but on historic rights.

Carlyle Thayer, geopolitical expert and professor-emeritus of Australia’s New South Wales Defense Academy explains it simply, “China is the first to discover, name, occupy and administer all the land features of the South China Seas.”

Chinese spokesperson Mao Ning completes the picture, “China’s sovereignty, rights and interests in the South China Sea have been established and solidly-grounded in the long course of history and law, which are in compliance with the UN Charter and international law, including UNCLOS.”

The most recent statutory construction of those historical facts and legal preeminence starts with the First Sino-Japanese War of July 1894 and the Treaty of Shimonoseki of 1895 that resolved it, the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and China’s involvement with the Allied Forces in World War II, flowing through the Cairo Conference of 1943 reinforced by the Potsdam Declaration of 1945, the Treaty of San Francisco of 1951 completed by the Treaty of Taipei of 1952, with the Peoples Republic of China as successor-in-interest by virtue of the United Nations One-China Resolution 2758, and finally recognized by the Philippines in its Joint Communique with PROC in 1975.

Arbitral affirmation

Contrary to Philippine propaganda, the PCA Arbitral Tribunal did not rule against China’s historic claims at all.

In Paragraph 272 of the award reads “In particular, the Tribunal emphasizes that nothing in this Award should be understood to comment in any way on China’s historic claim to the islands of the South China Sea.”

It also did not preclude China’s entitlements under UNCLOS: “Nor does the Tribunal’s decision that a claim of historic rights to living and non-living resources is not compatible with the Convention limit China’s ability to claim maritime zones in accordance with the Convention, on the basis of such islands.”

What may shock the Philippine officialdom now that the Philippine Supreme Court supports this Arbitral clarification:

Judicial confirmation

GR No. 187167 in declaring Republic Act 9522 (our latest baselines law) as not unconstitutional, distinguishes demarcating the Philippine maritime zones (and continental shelf) under UNCLOS, from delineating Philippine territory.

“UNCLOS and its ancillary baselines laws play no role in the acquisition, enlargement or, as petitioners claim, diminution of territory.

“Under traditional international law typology, States acquire (or conversely, lose) territory through occupation, accretion, cession and prescription, not by executing multilateral treaties on the regulations of sea-use rights or enacting statutes to comply with the treaty’s terms to delimit maritime zones and continental shelves.

“Territorial claims to land features are outside UNCLOS, and are instead governed by the rules on general international law. The last paragraph of the preamble of UNCLOS states that “matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by the rules and principles of general international law.”

This judicial interpretation, and our ensuing declaration with the United Nations on October 26, 1988, were necessary in order to reserve Philippine historic rights to territorial seas passed on to us by three colonial treaties, namely the Treaty of Paris of 1898, the Treaty of Washington of 1900 and the Convention Treaty of 1930 between the US and Great Britain.

We gained this delimitation earlier and outside of UNCLOS. Giving it up, our country would lose sovereignty over 804,140 square kilometers of territorial sea.

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

Reserving our historical rights but denying those of China is not only inconsistency and self-contradiction but hypocrisy at the highest level.

The fact stands and in parallel sum, the 2016 Arbitral award and our own Supreme Court, have sustained our Treaty limits and China’s historical rights to the South China Seas.

To be continued.

Next: China Calls Out DFA Lame Excuses

Adolfo Quizon Paglinawan

is the anchor of Ang Maestro – the Unfinished Revolution at Radyo Pilipinas1, co-host of Opinyon Ngayon at Golden Nation Network Television, a political analyst, and author of books.

His third book, The Poverty of Power will soon be off-the-press. It is a historiography of controversial issues of spanning 36 years leading to the Demise of the Edsa Revolution and the Rise of the Philippine Phoenix. Paglinawan’s past best sellers have been A Problem for Every Solution (2015), a characterization of factors affecting Philippine-China relations, and No Vaccine for a Virus called Racism (2020) a survey of international news attempting to tracing its origins. These important achievements earned for him to be named one of the 2021 international laureates for the Awards for the Promotion of Philippine-China Understanding. Ado, as he called for short, was a former press attaché and spokesman of the Philippine Embassy in Washington DC and the Philippines’ Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. Facebook

Email: contact@asiancenturyph.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/asiancenturyph/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AsianCenturyPH